History of Art Timeline⁚ A Comprehensive Guide

This comprehensive guide explores the vast world of art history, tracing the evolution of artistic styles, movements, and techniques across various periods. From prehistoric cave paintings to contemporary installations, this timeline delves into the key eras and influential artists who shaped the visual landscape.

Prehistoric Art (30,000 BC ⎻ 2500 BC)

This period encompasses the dawn of human artistic expression, predating the invention of writing and formal record-keeping. Prehistoric art provides a fascinating glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and rituals of early human societies. From the awe-inspiring cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira to the enigmatic megalithic structures of Stonehenge, these early forms of art reveal a profound connection to the natural world and a deep-seated desire to express human experience.

Cave paintings, a defining characteristic of this era, are found in various parts of the world. These vibrant depictions of animals, hunting scenes, and abstract symbols suggest a connection to ritual, storytelling, and perhaps even early forms of communication. The use of charcoal, ochre, and other natural pigments on cave walls speaks to the resourcefulness and artistic ingenuity of these early humans.

Beyond cave paintings, prehistoric art also includes a range of other forms, such as sculptures, engravings, and pottery. These objects, often found in archaeological contexts, offer further insights into the artistic practices and cultural beliefs of prehistoric societies. The intricate carvings on ivory figures, the symbolic designs on pottery vessels, and the monumental structures like Stonehenge all bear witness to the diverse and sophisticated artistic expressions of the prehistoric world.

Ancient Art (2500 BC ⎻ 500 AD)

Ancient art encompasses a vast and diverse array of artistic traditions from across the globe, spanning from the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley to the rise of classical Greece and Rome. This period witnessed a remarkable evolution in artistic techniques and a burgeoning of cultural expression, leaving behind a legacy of iconic monuments, sculptures, and paintings that continue to inspire and captivate audiences today.

Ancient Egyptian art stands out for its distinctive style, characterized by a focus on order, symmetry, and symbolism. Monumental pyramids, intricate hieroglyphic writing, and lifelike statues of pharaohs and deities embodied the Egyptian belief in eternal life and the power of the divine. The vibrant wall paintings adorning tombs and temples, depicting scenes from daily life, religious rituals, and the afterlife, offer a fascinating window into the beliefs and values of this ancient civilization.

In contrast, Greek art evolved through distinct periods, from the geometric style of the Archaic period to the idealized realism of the Classical era. The iconic marble sculptures of Greek gods and heroes, such as the Venus de Milo and the Doryphoros, exemplified the pursuit of beauty and perfection in human form. Greek architecture, characterized by the use of columns and intricate decorative elements, produced masterpieces like the Parthenon, a testament to the ingenuity of Greek engineers and architects.

The Roman Empire inherited and adapted many of the artistic traditions of Greece, adding its own distinct flavor. Roman art is known for its grandeur, practicality, and emphasis on realism. Roman architecture, with its monumental structures like the Colosseum and the Pantheon, showcased the empire’s power and engineering prowess. Roman sculpture, often depicting emperors, mythological figures, and everyday scenes, reflected a more pragmatic and down-to-earth approach compared to the idealized idealism of Greek art.

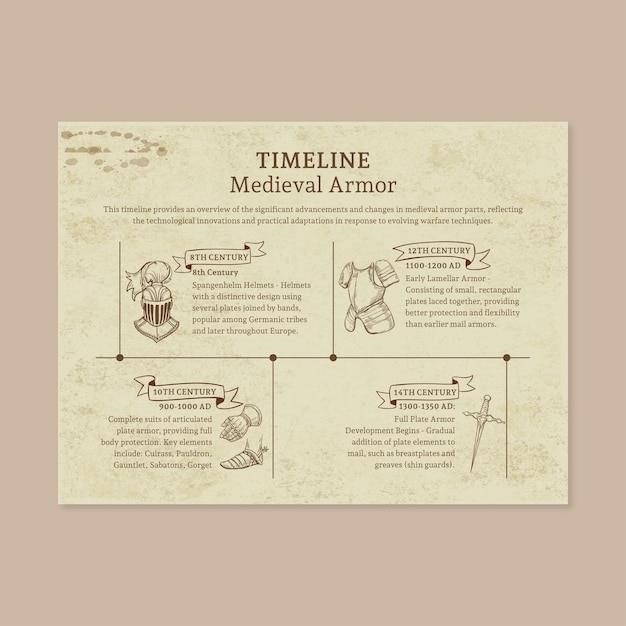

Medieval Art (500 AD ─ 1400 AD)

Medieval art, spanning roughly a millennium, witnessed a profound shift in artistic expression, reflecting the influence of the rise of Christianity and the flourishing of distinct regional styles across Europe. This era saw the emergence of iconic architectural masterpieces like cathedrals, churches, and monasteries, which served as centers of religious life and artistic innovation. The dominant artistic styles of the period—Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic—each played a crucial role in shaping the visual landscape of Europe.

Byzantine art, rooted in the Eastern Roman Empire, is characterized by its distinctive use of mosaics, intricate gold backgrounds, and stylized figures. The Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, with its awe-inspiring mosaics depicting biblical scenes and the Virgin Mary, stands as a prime example of Byzantine artistry. This style emphasized spiritual symbolism and a sense of otherworldly grandeur, reflecting the influence of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Romanesque art, which emerged in Western Europe, adopted a more robust and monumental style. Romanesque architecture, characterized by its thick walls, round arches, and heavy ornamentation, produced impressive churches like the Abbey Church of Cluny in France. Romanesque paintings, often found on church walls and ceilings, featured simplified figures and narratives from the Bible, emphasizing the importance of religious teachings.

Gothic art, flourishing from the 12th to 15th centuries, introduced a sense of lightness and verticality. Gothic cathedrals, with their soaring arches, pointed vaults, and stained-glass windows, exemplified the aspiration towards divine transcendence. The Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, with its intricate sculptures and breathtaking stained-glass narratives, serves as a prime example of this architectural style. Gothic art emphasized realism and emotion, depicting biblical stories and saints with greater naturalism and expressiveness.

Renaissance (1400 ⎻ 1600)

The Renaissance, a period of profound cultural and artistic rebirth, marked a pivotal shift in European history. It witnessed a renewed interest in classical Greek and Roman art, literature, and philosophy, leading to a flourishing of innovation and creativity across various disciplines. The Renaissance, meaning “rebirth,” embraced humanism, a philosophical movement that placed emphasis on human potential and the pursuit of knowledge.

Renaissance art, characterized by its emphasis on realism, perspective, and human anatomy, broke free from the conventions of medieval art. Master artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, renowned for their mastery of painting, sculpture, and architecture, redefined the artistic landscape. Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic “Mona Lisa” with its enigmatic smile and masterful use of sfumato, a technique that creates subtle transitions between light and shade, exemplifies the Renaissance’s pursuit of naturalism.

Michelangelo, renowned for his awe-inspiring sculptures like “David” and his magnificent frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, embodied the Renaissance’s ideals of human grandeur and artistic virtuosity. Raphael, celebrated for his harmonious compositions and masterful use of color, produced masterpieces like “The School of Athens,” a fresco that captures the spirit of Renaissance intellectualism. The Renaissance also saw the development of new techniques like oil painting, which allowed for richer colors and more detailed compositions. This era marked a significant turning point in art history, laying the foundation for the artistic advancements that followed.

Baroque (1600 ─ 1750)

The Baroque period, spanning from the early 17th to the mid-18th century, was a time of dramatic artistic expression and grandeur. It followed the Renaissance and was characterized by a heightened sense of movement, theatricality, and emotional intensity. The Baroque style emerged in Catholic Italy during the Counter-Reformation, a period of religious revival within the Catholic Church, and its influence spread throughout Europe. It was a period of great political and social change, marked by the rise of powerful monarchies and the increasing influence of the Catholic Church.

Baroque art celebrated the power and majesty of the Church and the state, often employing dramatic lighting, exaggerated forms, and elaborate compositions to evoke a sense of awe and wonder. Artists like Caravaggio, Bernini, and Rubens, masters of their respective mediums, epitomized the Baroque style. Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and shadow, known as chiaroscuro, created a sense of realism and heightened emotion in his paintings, as seen in his iconic “The Calling of St. Matthew.”

Bernini, a renowned sculptor and architect, created dynamic and expressive sculptures, such as “The Ecstasy of St. Teresa,” which captures the intensity of religious experience. Rubens, a master of the Baroque style, produced opulent and colorful paintings that celebrated the power and grandeur of the court, as seen in his famous “The Garden of Love.” The Baroque period witnessed a flourishing of architecture, with grand churches and palaces showcasing the opulence and drama of the style, exemplified by Bernini’s iconic St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Rococo (1750 ─ 1800)

The Rococo period, which emerged in the mid-18th century, marked a shift from the grandeur and formality of Baroque art to a more playful, delicate, and refined aesthetic. This style, characterized by its emphasis on elegance, grace, and a sense of lightness, found its roots in France and quickly spread throughout Europe. It reflected the changing social and cultural landscape of the time, with a focus on the aristocracy and their opulent lifestyle. The Rococo era was a time of intellectual and artistic ferment, where the Enlightenment’s ideals of reason and individual freedom were gaining traction. However, it also witnessed the growing social unrest that would eventually lead to the French Revolution.

Rococo art celebrated the beauty and pleasures of life, with a focus on sensual curves, playful asymmetry, and delicate pastel colors. Artists like Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard, known for their exquisite portraits and charming scenes of courtly life, were masters of this style. Watteau’s “Embarkation for Cythera,” a masterpiece of Rococo painting, depicts a romantic and idyllic scene of aristocratic pleasure, while Boucher’s “The Toilet of Venus” exemplifies the style’s emphasis on sensuality and beauty. Rococo architecture, with its ornate interiors, delicate stucco work, and whimsical decorative elements, created a sense of intimacy and elegance. The Palace of Versailles, with its grand gardens and lavish interiors, is a prime example of Rococo architecture. The Rococo style also influenced furniture, fashion, and decorative arts, contributing to the overall aesthetic of the era.

Neoclassicism (1750 ─ 1850)

Neoclassicism, a major artistic movement that emerged in the mid-18th century, represented a revival of classical art and architecture from ancient Greece and Rome. This style, characterized by its emphasis on order, reason, and clarity, was a direct reaction to the excesses of the Rococo period and reflected the intellectual currents of the Enlightenment. Neoclassical artists and architects sought to emulate the ideals of beauty, harmony, and balance that they found in classical art, believing that these principles embodied universal truths and moral values. The movement’s influence extended far beyond the art world, impacting architecture, literature, music, and even political thought.

Neoclassical art emphasized idealized forms, simple compositions, and a focus on historical and mythological themes. Artists like Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Antonio Canova were prominent figures in this movement. David’s “Oath of the Horatii,” a powerful painting depicting Roman patriotism and sacrifice, is a prime example of Neoclassical art. The emphasis on clarity, order, and a sense of monumentality is evident in the work of Canova, whose sculptures, like “Pauline Borghese as Venus Victrix,” embodied the ideals of classical beauty and grace. Neoclassical architecture, with its emphasis on symmetry, columns, and pediments, found expression in buildings like the Pantheon in Paris and the United States Capitol Building. This style, with its focus on reason and restraint, became a symbol of republicanism and a testament to the enduring power of classical art.

Romanticism (1800 ─ 1850)

Romanticism, a powerful artistic movement that flourished during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, represented a profound shift in artistic sensibility. Rejecting the rationalism and restraint of Neoclassicism, Romanticism embraced emotion, imagination, and the individual experience. This movement was fueled by a fascination with the sublime, a sense of awe and wonder inspired by nature, the supernatural, and the human spirit. Romantic artists sought to capture the power and beauty of the natural world, often depicting dramatic landscapes, stormy seas, and majestic mountains. They also explored themes of passion, love, and the darker aspects of the human psyche, delving into the depths of human emotions and the complexities of the human condition. The movement had a profound impact on literature, music, painting, and sculpture, shaping the artistic landscape of the era.

Romantic painters, such as Eugène Delacroix, Caspar David Friedrich, and J.M.W. Turner, were masters of evoking emotion through their art. Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People,” a powerful depiction of the July Revolution in France, captures the energy and passion of the movement. Friedrich’s “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog,” a haunting image of a solitary figure gazing out at a vast, misty landscape, exemplifies the Romantic fascination with nature and the human spirit. Turner’s breathtaking seascapes, like “The Slave Ship,” are characterized by their dramatic use of light and color, conveying a sense of awe and the power of nature. Romantic sculpture, as exemplified by the works of Auguste Rodin, explored themes of passion, struggle, and the human condition. Rodin’s “The Thinker,” a powerful image of a brooding figure lost in contemplation, embodies the Romantic spirit of introspection and emotional depth. Romanticism, with its embrace of emotion, imagination, and the individual experience, left an indelible mark on art history, paving the way for the artistic revolutions that followed.

Realism (1840 ⎻ 1900)

Emerging as a reaction against the idealized and often sentimental nature of Romanticism, Realism emerged in the mid-19th century as a powerful artistic movement that sought to portray the world as it truly was. Realist artists rejected the romantic notions of beauty and grandeur, choosing instead to depict everyday life, ordinary people, and the realities of the working class. They focused on portraying the world with accuracy and objectivity, often depicting scenes of poverty, labor, and social injustice. Realism was a movement rooted in observation and a desire to capture the truth of the human condition. The movement’s impact was felt across various art forms, from painting and sculpture to literature and theater.

Realist painters, such as Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, and Honoré Daumier, became known for their unflinching depictions of everyday life. Courbet’s “The Stonebreakers,” a powerful image of two men breaking stones on a road, exemplifies the movement’s focus on depicting the harsh realities of labor. Millet’s “The Gleaners,” a poignant image of peasant women gathering scraps of grain after the harvest, captures the struggles of the working class. Daumier’s satirical caricatures, often depicting the injustices of society, exposed the flaws of the political and social system. Realist sculpture, as exemplified by the works of Auguste Rodin, also sought to capture the truth of the human form and experience. Rodin’s “The Kiss,” a passionate portrayal of two lovers embracing, depicts the complexities of human emotion with honesty and realism. Realism, with its focus on truth, objectivity, and the depiction of everyday life, marked a significant turning point in art history, paving the way for the emergence of new movements and artistic innovations.

Impressionism (1860 ⎻ 1900)

Impressionism, a pivotal movement in art history, emerged in late 19th-century France, challenging traditional artistic conventions and forever altering the landscape of painting. This revolutionary movement embraced a fresh approach to capturing the fleeting effects of light and color, abandoning the meticulous detail and academic precision of earlier styles. Impressionist artists, such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, sought to capture the ephemeral beauty of the world around them, focusing on the subjective and instantaneous experience of light and color. They applied paint in short, broken brushstrokes, creating a shimmering surface that reflected the play of light on objects and landscapes. Their canvases became a celebration of the beauty of everyday life, capturing the vibrant colors and fleeting moments of Parisian streets, countryside landscapes, and social gatherings.

Monet’s iconic series of “Water Lilies” paintings, with their luminous reflections and ethereal atmosphere, epitomize the Impressionist pursuit of capturing the fleeting beauty of nature. Renoir’s joyful paintings of Parisian life, such as “Bal du moulin de la Galette,” capture the energy and vibrancy of social gatherings, while Degas’s innovative studies of dancers, with their fluid movements and dynamic compositions, revolutionized the depiction of the human figure. Pissarro’s landscapes, with their atmospheric perspectives and subtle color harmonies, offer a glimpse into the beauty of the natural world. Impressionism, with its focus on capturing the essence of the moment and the subjective experience of light and color, had a profound impact on the development of modern art, paving the way for the emergence of new artistic styles and movements. Its legacy continues to inspire artists today, as they explore the boundless possibilities of color, light, and the fleeting beauty of the world around us.